Denmark’s Offshore Wind Market: Lessons, Reforms and New Momentum

Denmark, a world leader in offshore wind, faces a critical juncture. After a failed auction for 6 GW of projects in 2024, the Danish government has reinvented its approach. A new, market-adapted tender for 2.8 GW leverages state-backed Contracts for Difference (CfD), environmental incentives, and robust government-industry dialogue. Denmark is attempting to reaffirm its leadership in the offshore wind space.

“The Danish Government will go all in to establish the conditions that can enable a rapid scale up of Danish offshore wind.” Lars Aagaard -- Minister for Climate, Energy and Utilities

The following analysis is from CoralPoint and Brinckmann’s market intelligence and policy experts.

Introduction

Denmark has long symbolised offshore wind innovation, commissioning the world’s first commercial offshore wind farm in 1991. The nation had ambitions for 14 GW of capacity by 2030, with unparalleled influence over the European energy transition. Yet, the collapse of its 2024 offshore auction revealed market uncertainty and misalignment of incentives, prompting a substantial reset by policymakers.

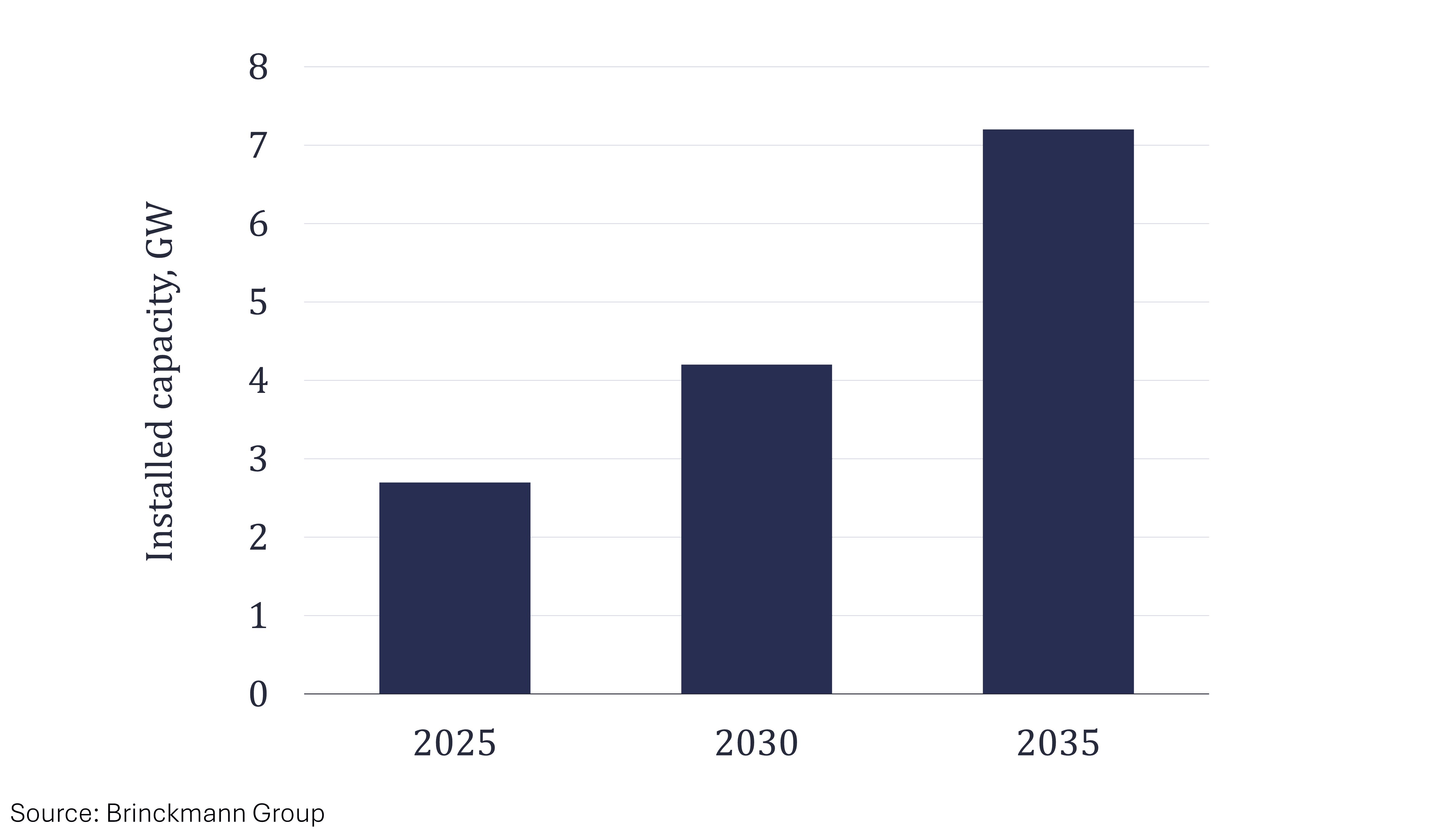

To contextualise the significance of the 2.8 GW tender, current market forecasts provide valuable perspective on Denmark’s trajectory. Research from CoralPoint and Brinckmann, drawing on comprehensive offshore market intelligence, indicates:

- Cumulative installed capacity by year-end 2024: 2.7 GW

- Forecast additional capacity (2025–2030): 1.5 GW

- Projected cumulative capacity by 2030: 4.2 GW

We anticipate that the 2.8 GW from the current tender, inclusive of overplanting, will be installed by end-2035. Additionally, a further 160 MW project is forecasted to come online in 2032, bringing the cumulative installed offshore capacity to approximately 7.2 GW (+ overplanting) by end of 2035. Whilst this represents a shortfall compared to aspirational targets, it is still an important increase.

Exhibit 1: Denmark offshore wind forecast

Market Setback and Government Response

The Failed 2024 Auction

In December 2024, Denmark’s tender for six new wind farms, targeting 6 GW, received no bids. Developers cited untenable commercial risk and rigid concession payment requirements, while government mandates on state co-ownership raised barriers. According to the Ministry of Climate, Energy and Utilities:

“A market dialogue…revealed the reasons for the absence of bids…the aim [now] is adapting the tender framework to market conditions, for example by altering the risk allocation.”

Policy Overhaul: The 2.8 GW CfD Tender

Responding to both market realities and climate targets, a broad political coalition agreed in May and November 2025 on a re-tendering, adapting the framework through:

- A two-sided CfD support scheme (20 years’ duration)

- Flexible installation timelines (2032–2034 deadlines)

- State payment cap of DKK 55.2 billion (€7.3 billion)

- Enhanced sustainability criteria (blade recyclability, nature-inclusive design)

- Social and cybersecurity compliance requirements

Rather than doubling down on existing frameworks, the Danish Energy Agency conducted extensive market dialogues with developers, turbine manufacturers, and infrastructure operators to identify barriers. The Agency explained:

“The tenders are based on thorough market dialogues... and include, among other things, state subsidies and greater flexibility for developers to increase the likelihood of qualified bids.” Danish Energy Agency

Mechanics of the New Tender

CfD: Risk Reduction through State Support

Denmark’s new Contract for Difference (CfD) model for offshore wind tenders represents a significant departure from traditional practice in European markets, using mechanisms to address industry challenges and incentivise investment. Key features include:

- Capability-Based CfD: Unlike most traditional CfDs, which settle on realised generation, Denmark’s model bases subsidy payments on potential production capability given prevailing wind conditions. This method helps to mitigate distortions in the electricity market by reflecting what the project could have produced, not strictly what it actually delivered.

- Two-Way, Market-Linked Structure: The scheme guarantees the developer a fixed price per kilowatt hour; if market prices fall below the strike price, the government pays the difference; if prices rise above, the developer pays the state. This reduces risk for concessionaires and answers specific requests from the market for greater certainty, especially amidst volatile energy pricing.

- Tender Award Mechanism: Strike prices are set competitively, with bidders offering the lowest price winning the tender. This approach focuses purely on price, ensuring the lowest expected subsidy payments.

- Enhanced Flexibility: Penalty schemes for project delays are more relaxed in the first two years post-commissioning, similar to Dutch and Belgian approaches. The tender also removes financial eligibility requirements to broaden market participation, and permits “free overplanting” (maximising capacity in designated seabed areas).

- Direct Cost Coverage: The Danish state will absorb certain key costs, such as mitigation measures for Danish Defence and pre-investigation studies, previously borne by developers. This increases project viability and reduces barriers to entry.

- Strict Subsidy Cap: The model includes a total subsidy cap, limiting Denmark’s ultimate fiscal exposure. However, actual payments may be lower depending on market electricity prices over the 20-year period. There is no cap on developer payments back to the state if market prices exceed the strike price.

Denmark’s capability-based CfD represents a significant policy innovation, positioning the country as a first mover internationally. Capability-based CfDs have been discussed conceptually in European regulatory circles, but no other country currently operates an offshore wind CfD following this approach at commercial scale. This distinction carries strategic advantage: Denmark demonstrates policy leadership and commitment to innovation. However, it also introduces implementation risks that warrant careful monitoring.

The fundamental challenge is that payments are tied to modelled capability rather than realised generation, creating layers of developer exposure not present in traditional CfDs. Developers bear the risk of under- or over-performance relative to agreed capability models, which could influence bid behaviour and raise subsidy costs. Determining capability requires consistent assumptions about wind resources, turbine availability, curtailment conditions, and grid constraints, creating potential room for disputes and disagreements between developers and authorities on methodology, data, and assumptions. Additionally, capability-based payments decouple revenue from actual plant dispatch and operational optimisation, potentially weakening incentives for high availability, proactive maintenance, or system-supportive behaviour unless explicit mitigation measures (e.g., availability bonuses or penalties) are embedded in contract terms.

Most significantly, no other country has implemented capability-based CfDs commercially, meaning limited empirical evidence exists on their performance across full asset life cycles. Denmark will be closely observed as a testbed for this model, providing valuable learning for European energy policy, but also carrying genuine uncertainty about long-term capability determination, technological change, and alignment with grid needs over 20-year contract periods.

Scope

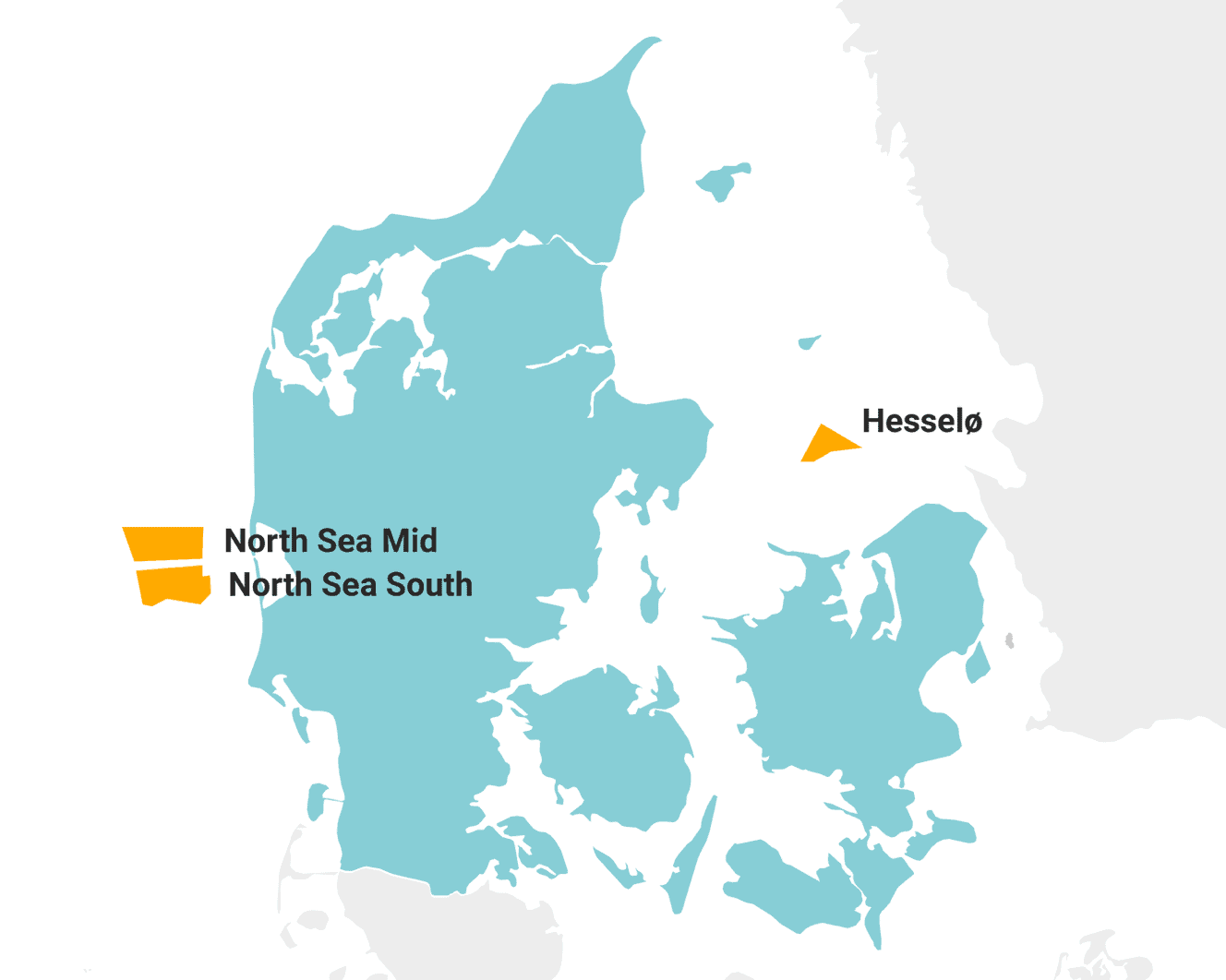

The tender covers three sites:

- North Sea Mid (1 GW, completion by end-2032)

- Hesselø in the Kattegat (800 MW, completion by end-2032, nature-inclusive design required)

- North Sea South (1 GW, completion by end-2034)

Exhibit 2: Denmark’s latest offshore wind tender areas (image from Danish Energy Agency)

Sustainability Incentives

The tender is designed with a two-track process. The first track is the prequalification requirements. All bidders must meet minimum sustainability and social responsibility thresholds to qualify for the auction. These include:

- Third-party verified Environmental Product Declarations (EPDs) and life cycle assessments for central offshore wind farm components.

- Recyclable turbine blades with Environmental Technology Verification documentation required by the construction start-up deadline.

- Environmental monitoring programs that developers must establish and maintain throughout the project lifecycle.

- Protection against social dumping, including requirements for apprenticeships and supply chain responsibility.

- Nature-inclusive design for the Hesselø project specifically – a mandatory requirement integrated into the tender conditions, necessitating a framework combining marine habitat conservation into offshore infrastructure design.

- Cybersecurity compliance, with the Danish Energy Agency entitled to request documentation at any point.

Once bidders pass prequalification, the competitive element is determined solely by price.

The Broader Danish Ambition

Denmark’s government states its “ambition of 14 GW [offshore wind] by 2030, and at least 35 GW by 2050”, striving for both climate leadership and European grid integration. The new tender is projected to power around three million homes and anchor Denmark’s competitive position as North Sea countries pledge 120 GW collectively by 2030.

The Ministry’s latest climate action plan reaffirms these priorities, noting, “This adjusted process will result in delays. However, it does not affect the 70% [emissions reduction] goal.”

Challenges and Outlook

Despite progress, obstacles remain. The tender still requires EU state-aid approval, and grid connection logistics represent open risk. As the government concedes, “A grid connection option of at least 1 GW is being prepared, but it is not clear how this will be reflected in the final tender conditions.”

Denmark’s existing offshore transmission infrastructure, whilst advanced, faces capacity constraints given projected renewable energy penetration levels (80%+ electricity generation by 2030). Transmission expansion timelines must align with offshore wind commissioning to prevent curtailment of otherwise dispatchable renewable generation.

Dialogue with industry actors appears permanent: future policy recalibration is likely as Denmark balances climate ambition, market demands, and public accountability.

Conclusion

Denmark’s revised offshore wind tender reflects a mature, market-responsive policy environment. The move towards CfDs, flexible deadlines, and sustainability objectives demonstrates a willingness to learn from setbacks and maintain leadership in offshore wind.

The capability-based CfD model, whilst forward-thinking, introduces novel risks that carry no international precedent. The challenges of operating a system with no comparable operational experience elsewhere requires close industry monitoring and willingness to adjust policy as Denmark’s projects move into operation.

The coming years will test whether policy evolution can translate into actual gigawatts – and keep Denmark atop the offshore wind leaderboard.

Sources:

“Agreement on tender frameworks for three offshore wind farms.” (Danish Ministry of Climate, Energy and Utilities, 19 May 2025) https://www.kefm.dk/Media/638832600830188706/Aftale%20om%20udbudsrammer%20for%20tre%20havvindmlleparker.pdf

“Adjustments in the Agreement on tender frameworks for three offshore wind farms from 19 May 2025.” (Danish Ministry of Climate, Energy and Utilities, 7 Nov 2025). https://www.kefm.dk/Media/638980628308630236/Overblik%20over%20justeringer%20i%20Aftale%20om%20udbudsrammer%20for%20tre%20havvindmlleparker.pdf

“The Danish Energy Agency opens tenders for three new Danish offshore wind farms.” (Danish Energy Agency, 20 Nov 2025) https://ens.dk/en/press/danish-energy-agency-opens-tenders-three-new-danish-offshore-wind-farms

“The Danish Government invests in more offshore wind and green hydrogen.” Danish Ministry of Climate, Energy and Utilities, 31 Jan 2025. https://www.en.kefm.dk/news/news-archive/2025/jan/the-danish-government-invests-in-more-offshore-wind-and-green-hydrogen-

“Presentation of Danish climate policy.” (Henrik Silkjær Nielsen, Renewable Energy Institute webinar, 7 Feb 2025) https://www.renewable-ei.org/pdfdownload/activities/DK_climate_policy_20250207.pdf