Powering Britain’s Renewable Energy Future Through Technology and Industrial Strategy

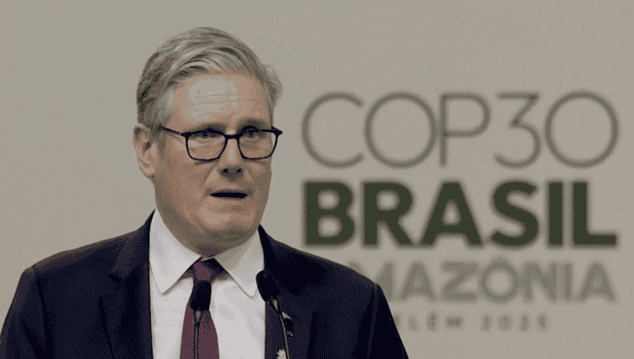

"Today, sadly that consensus is gone," Prime Minister Keir Starmer told world leaders at COP30 in Belém, Brazil, on 6 Nov 2025 in the context of the drive to net zero. Ten years after nations united in Paris around climate science that remains "unequivocal," the UK now finds itself navigating a fractured global landscape where some argue "this isn't the time to act" and that "tackling climate change can wait."

Exhibit 1: “The UK is all in” for the energy transition, Prime Minister Keir Starmer

Yet Britain’s response has been unambiguous. “My message is that the UK is all in,” Starmer declared, framing the clean energy transition not as burden but as “an immense opportunity to be seized”, to make energy “a source not of vulnerability, but of strength” and “an engine to create thousands of new jobs, bring down household bills, and end once and for all our exposure to volatile fossil fuel markets and dictators like Putin who seek to weaponise them.” This commitment arrives precisely as the independent Climate Change Committee (CCC) confirmed in June 2025 that the UK has achieved a 50.4% reduction in emissions since 1990, establishing Britain as the first major economy to halve its greenhouse gas footprint.

The timing proves critical. Even as COP30 convenes to accelerate commitments made under the Paris Agreement a decade earlier, host nation Brazil simultaneously expands fossil fuel extraction, having approved Petrobras exploratory drilling at the Amazon’s mouth weeks before the summit. A significant populist backlash against net zero policies has gathered momentum across developed economies, with organised campaigns characterising clean energy transitions as “costly elitist plots against working people” despite contradicting evidence from economists and independent institutions.

For Britain, this global context renders the renewable energy and power-to-X transition simultaneously more strategically important and more politically fragile. Recent government policy documents, including the Carbon Budget and Growth Delivery Plan and the government’s formal response to CCC recommendations, establish comprehensive frameworks for renewable electricity deployment, hydrogen commercialisation and industrial decarbonisation, underpinned by £63bn in public investment intended to catalyse over £50bn in private capital. Yet the CCC’s 2025 assessment identified persistent delivery risks, warning that “plans remain insufficient” across significant sectors while noting that success relies on “urgent action” in ten critical priority areas.

Exhibit 2: CCC progress report and UK Government response

The challenge is not policy ambition or technical feasibility but rather the political economy of energy transition during a period of genuine economic anxiety, rising inequality and visible tensions between climate objectives and immediate living standards concerns. Starmer’s COP30 speech directly addressed this tension, challenging sceptics: “Can energy security wait too? Can billpayers wait? Can we win the race for green jobs and investment by going slow? Of course not.” How effectively Britain navigates this transition, including delivering on offshore wind deployment, establishing hydrogen as a genuine industrial fuel, and enabling industrial electrification without imposing disproportionate costs on communities, will significantly influence both global climate outcomes and whether populist resistance to net zero can be overcome through demonstrated economic benefits.

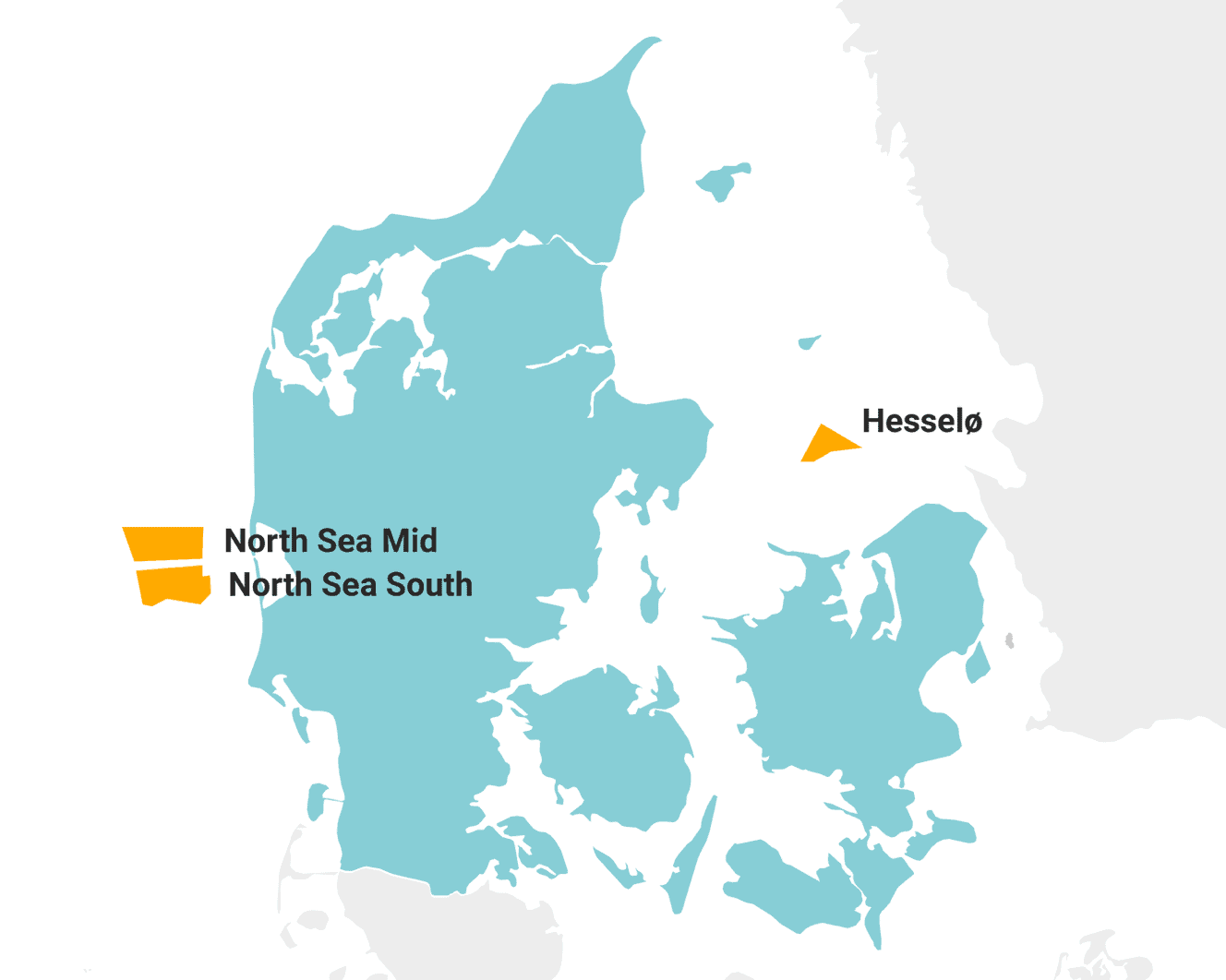

Clean Power 2030: The Offshore Wind Challenge

The government’s Clean Power 2030 mission sets an ambitious trajectory: 95% low-carbon electricity generation within five years, with offshore wind capacity reaching 43-51 GW by decade’s end. This represents approximately tripling current installed capacity of 15 GW; a deployment challenge without precedent in British energy history.

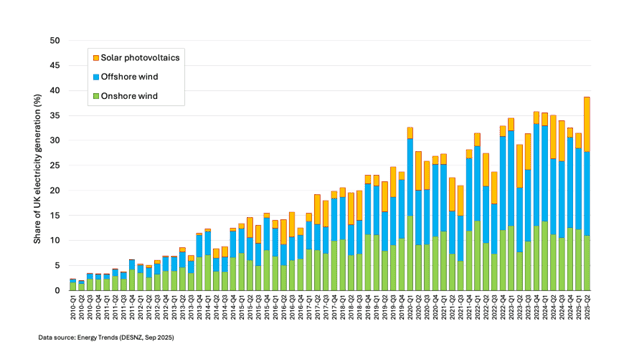

Recent performance data demonstrates why offshore wind commands such strategic importance. Independent energy analysis shows Great Britain has operated on 100% clean power for a record 87 hours in 2025 to date, up dramatically from just 2.5 hours in 2021. These fossil-fuel-free periods prove that variable renewable grids can deliver reliable electricity when capacity, storage and interconnection align favourably.

Exhibit 3: The remarkable rise of renewable power generation in the United Kingdom

Offshore wind contributed 17.2% of UK electricity in 2024, with the sector already supporting 32,000 jobs nationwide and projected employment growth to 100,000 by 2030. Each large offshore wind farm adds £2-3bn to the economy, with the cumulative investment opportunity worth up to £92bn by 2040.

The world’s largest offshore wind farm, the 3.6 GW Dogger Bank project currently under construction off Yorkshire, exemplifies the economic magnitude of Britain’s offshore wind buildout. Independent economic analysis reveals Dogger Bank will contribute £6.1bn to UK GDP during its operational lifetime, with direct spend in North-East England and Yorkshire exceeding £3bn and full-time equivalent jobs reaching 3,600 across the UK during peak construction.

Offshore Wind Economics: From Subsidy to Savings

The economic case for offshore wind has fundamentally transformed over the past decade. Comprehensive analysis covering 2010-2023 reveals that wind energy delivered £147.5bn in total economic advantage to the UK, comprising £14.2bn from lower electricity costs and £133.3bn from reduced natural gas prices. After accounting for £43.2bn in wind subsidies, UK consumers saved £104.3bn compared to a counterfactual scenario without wind investment.

This net consumer benefit stems from wind energy’s displacement of gas generation. Every megawatt-hour generated by offshore wind represents gas that need not be imported, reducing exposure to volatile international energy markets. During 2025’s record solar output months, avoided gas imports totalled approximately £600m while preventing six million tonnes of CO₂ emissions.

The Contracts for Difference (CfD) mechanism has driven remarkable cost reductions. Strike prices that exceeded £140/MWh in early allocation rounds have fallen below £50/MWh in recent auctions, demonstrating rapid technology maturation and supply chain efficiency gains. This cost trajectory positions offshore wind as one of the lowest-cost sources of new electricity generation, with levelised costs continuing to decline as turbine sizes increase and installation techniques improve.

Supply Chain: The Industrial Opportunity

Britain’s offshore wind sector has cultivated domestic supply chain capabilities, with current UK content estimated at 32% and industry commitment to reach 60% by 2030. The recently published Industrial Growth Plan charts a detailed pathway to triple offshore wind manufacturing capacity over the next decade, identifying specific supply chain investments that would create an additional 10,000 jobs annually and boost the economy by £25bn through 2035.

Critical supply chain components where the UK demonstrates existing strength include blade and tower manufacture, cable supply, and operations and maintenance services. The plan identifies strategic growth opportunities in installation vessels, foundation manufacturing, and power electronics; areas where developing domestic capabilities could substantially increase UK content while reducing dependence on international suppliers.

Government commitments support this supply chain development. Great British Energy’s £1bn Clean Energy Supply Chain Fund provides targeted capital for manufacturing facility investment, while the Clean Industry Bonus offers enhanced support for offshore wind projects demonstrating substantial UK content. Regional concentrations are emerging: Teesside developing as a manufacturing hub, the Humber specialising in installation and maintenance, and Scottish ports positioning for floating wind fabrication and assembly.

Environmental science investment has proven remarkably cost-effective in enabling offshore wind deployment. Research funding delivered through government research councils since 2000 has generated £3.3bn in economic value via data, modelling and environmental impact assessment capabilities used throughout the sector, representing a 23-fold return on public investment. Future value attributable to this research is projected at an additional £3.6bn over the next 25 years.

Floating Offshore Wind: From Frontier Technology to Commercial Scale

Floating platforms, held in position by mooring systems rather than seabed foundations, unlock the 80% of global offshore wind resources beyond conventional installations. Water depths exceeding 60 metres become accessible, enabling deployment in regions with stronger, more consistent wind resources that could achieve 5-10% higher capacity factors than nearshore fixed installations. This capability is strategically essential: fixed-bottom installations have largely exhausted prime shallow-water sites, making deep-water floating developments critical for Britain’s target of 43-51 GW by 2030.

The UK has cultivated floating wind across geographically dispersed regions. The Celtic Sea hosts the Crown Estate’s Round 5 projects – Equinor and the Gwynt Glas joint venture (EDF Renewables UK and ESB) – delivering 3 GW off South Wales by the late 2030s, supported by £400m in supply chain investment and 5,300 construction jobs. Simultaneously, Scotland is emerging as a critical hub through dedicated government investment: the Port of Cromarty Firth received £55m through the Floating Offshore Wind Manufacturing Investment Scheme (FLOWMIS) to enable commercial-scale turbine fabrication by 2028, supporting 1,000 skilled jobs. Scottish waters benefit from Europe’s strongest wind resources and the UK’s most experienced offshore maritime workforce, positioning accelerated delivery compared to Celtic Sea projects.

Unlike fixed foundations requiring expensive jack-up crane vessels for installation, floating structures assemble completely in port and tow to sites, reducing weather exposure and leveraging existing shipyard capacity. This logistical advantage positions Scottish ports and northern industrial regions for disproportionate supply chain opportunities. The Floating Wind Joint Industry Programme’s coordination of 16 leading developers systematically addresses mooring system reliability, electrical integration and installation logistics, accelerating technology maturation toward cost parity with fixed-bottom wind by 2035.

However, formidable headwinds impede deployment timelines. Current floating costs of approximately £145/MWh substantially exceed fixed-bottom wind at £95/MWh, with cost reduction dependent on precisely the scaling Britain is attempting. Mooring system reliability remains unresolved: DNV estimates failure rates of 0.1-2%, substantially above industry targets, with manufacturing defects and fatigue risks potentially generating material remediation costs during critical early operational years.

Permitting and financing create compounding deployment constraints. Offshore wind projects typically require a decade of environmental impact assessment and consenting before construction begins, a timescale that floating projects, lacking established regulatory precedent, may exceed substantially. The AR7 CfD auction excluded floating wind projects without full planning consent, effectively barring most advanced floating projects from competing for government support and mechanically limiting floating wind’s contribution to 2030 targets. Elevated CfD strike prices (around 10% higher than the preceding auction) reflect capital cost inflation and tight financing conditions rather than technology maturation, signalling that current economic conditions insufficiently support floating wind commercialisation at the scale Britain requires.

Supply chain investors face insufficient policy certainty to justify large-scale manufacturing capacity expansion. Fragmented financing sources, to-be-determined business models and intermittent CfD allocation rounds create planning uncertainty that delays port infrastructure, electrolyser production and specialized vessel construction.

Floating wind will undoubtedly comprise material UK offshore capacity by 2040-2050. Whether it contributes meaningfully to 2030 targets depends on accelerated regulatory streamlining, development-stage financial instruments and sustained CfD allocations specifically ring-fenced for floating projects – policy innovations matching the technological progress already demonstrated in Celtic Sea and Scottish waters.

Grid Infrastructure: Connecting Generation to Demand

Offshore wind capacity proves meaningless if generated electricity cannot reach consumers. The UK faces an £80bn transmission network investment requirement over the next decade, upgrading and expanding high-voltage infrastructure to accommodate clean power generation growth. This network buildout represents both critical enabler and potential bottleneck for renewable deployment.

Grid connection delays have emerged as one of offshore wind’s most persistent challenges, with some projects receiving connection offers for the late 2030s, effectively rendering them financially unviable. Reform initiatives including the shift from “First Come, First Served” to “First Ready, First Connected” connection queue management prioritise projects demonstrating planning consent and project readiness, potentially accelerating viable project timelines by 5-7 years.

The Planning and Infrastructure Bill promises streamlined approval processes for Nationally Significant Infrastructure Projects, including both offshore wind generation and transmission infrastructure connecting projects to the grid. Combined with National Grid’s accelerated offshore coordination scheme, these reforms should transform grid connection from existential threat to manageable project milestone.

Offshore ring-main concepts, where multiple wind farms connect to shared transmission infrastructure rather than individual radial connections, offer substantial efficiency gains and cost reductions. Such concepts have been proposed for many years, but have had little traction in Britains laissez-faire market. The government and Ofgem are finally progressing regulatory frameworks enabling these coordinated approaches, potentially saving billions in duplicated transmission assets.

Solar: The Distributed Generation Success

While offshore wind captures strategic attention, solar power has emerged as Britain’s unexpected renewable success story. UK solar capacity reached 20.2 GW in 2024, with generation surging 42% year-on-year during 2025’s sunniest spring on record. Peak solar output reached 13.2 GW, supplying 40% of national electricity demand in a single half-hour period.

Solar’s distributed nature complements offshore wind’s concentrated generation profile. Rooftop and ground-mounted solar installations enable generation close to consumption, reducing transmission losses and enhancing grid resilience. Government commitments to install solar on 250 schools, 260 NHS sites and 15 military facilities through Great British Energy demonstrate recognition of solar’s rapid deployment potential and immediate bill-reduction benefits.

Combined wind and solar generation exhibits valuable complementarity. Winter months deliver peak wind output while summer sunshine drives solar generation, with spring and autumn providing balanced contributions from both technologies. This seasonal diversity reduces the storage and backup capacity required to maintain reliable electricity supply throughout the year.

Hydrogen and Power-to-X: The Hard-to-Abate Solution

Direct electrification proves optimal for most energy applications; electric vehicles replacing combustion engines, heat pumps displacing gas boilers, electric arc furnaces substituting for fossil-fueled steel production. Yet certain sectors face technical or economic barriers to battery-electric solutions: heavy goods vehicles operating long distances, shipping and aviation requiring high energy-density fuels, industrial processes demanding high-temperature heat, and chemical industry feedstocks.

For these hard-to-abate applications, power-to-X technologies, particularly green hydrogen produced via renewable-powered electrolysis, provide essential decarbonisation pathways. The UK government has committed over £2bn in revenue support and £90m in capital expenditure for 11 green hydrogen projects under Hydrogen Allocation Round 1 (HAR1), with projects becoming operational between 2025-2028 and creating over 700 direct jobs during construction and operation.

HAR2 attracted 87 applications, with 27 projects shortlisted across England, Scotland and Wales, demonstrating robust industry interest despite early-stage market conditions. The government aims to launch HAR3 by 2026 and HAR4 from 2028, signaling sustained commitment to scaling hydrogen production and enabling supply chain investment.

Beyond hydrogen production, the government has confirmed over £500m for Britain’s first regional hydrogen transport and storage networks, operational from 2031. This infrastructure proves critical for connecting hydrogen production facilities with dispersed industrial users and enabling hydrogen-to-power generation; flexible, low-carbon dispatchable electricity generation complementing variable renewables.

Power-to-X encompasses technologies beyond hydrogen alone. Renewable electricity converts into synthetic methane, methanol, ammonia and sustainable aviation fuels, each serving specific applications. The UK’s Sustainable Aviation Fuel Mandate, effective January 2025, requires 2% SAF blending initially, rising to 10% by 2030 and 22% by 2040, creating demand pull for power-to-X derived aviation fuels.

In shipping, power-to-X-derived ammonia and methanol provide carbon-neutral alternatives compatible with modified engines. The Maritime Decarbonisation Strategy targets at least 30% reduction in domestic shipping fuel lifecycle emissions by 2030, supported by forthcoming fuel regulations and emissions pricing mechanisms.

Industrial Electrification: Addressing the Price Barrier

While power-to-X addresses genuinely hard-to-abate sectors, direct electrification must constitute the primary industrial decarbonisation pathway wherever technically feasible. Independent analysis projects electricity could meet 61% of industrial energy demand by 2040, up substantially from current levels, through widespread adoption of electric furnaces, industrial heat pumps and electric process heating.

However, Britain’s industrial electrification confronts a fundamental barrier: electricity costs approximately four times gas on an energy-equivalent basis for typical industrial consumers. This pricing disparity stems primarily from policy costs loaded onto electricity bills, including legacy renewable obligations, feed-in tariffs and network charges, making fossil fuel combustion economically rational even where electric alternatives exist.

Government initiatives including the British Industrial Competitiveness Scheme will reduce electricity costs by up to £40/MWh for 7,000 energy-intensive firms, while the British Industry Supercharger increases transmission charge discounts from 60% to 90% for the most energy-intensive operations. Yet broader policy cost rebalancing proves essential: removing legacy charges from electricity bills and shifting them to general taxation or gas prices could reduce the electricity-to-gas price ratio from around 4:1 to 2-3:1, fundamentally transforming industrial investment decisions.

This single policy intervention, requiring no new technology development, could unlock billions in industrial electrification investment while making heat pump deployment economically compelling for commercial buildings and industrial processes. The Climate Change Committee identifies this electricity price reform as the highest priority recommendation for achieving carbon budget targets.

Carbon Capture: Enabling Power-to-X and Industrial Resilience

For power-to-X technologies requiring carbon feedstocks, such as synthetic fuel production, and for blue hydrogen production via steam methane reforming, carbon capture, utilisation and storage (CCUS) infrastructure proves essential. The UK has made tangible progress, reaching financial close on CO₂ transport and storage infrastructure for both Track-1 clusters (HyNet and East Coast Cluster) during 2024-2025.

This infrastructure, capable of storing up to 8.5 million tonnes of CO₂ annually across both clusters, enables not only industrial carbon capture but also bioenergy with carbon capture and storage and direct air carbon capture; engineered greenhouse gas removal technologies critical for balancing residual emissions from genuinely hard-to-abate sectors.

The government’s commitment of up to £21.7bn over 25 years for CCUS and hydrogen projects in Track-1 clusters represents substantial public investment in nascent technologies. However, delays in finalising business models for specific industrial and engineered removal projects create delivery risks, with increasing likelihood that initial deployment timeframes will extend beyond original 2028-2030 targets.

Skills Development: The Constraining Resource

Ambitious deployment targets prove meaningless without the workforce to deliver them. The UK faces acknowledged skills shortages across renewable energy sectors, from offshore wind installation technicians to electrolyser engineers to power systems specialists.

The diversity of roles within offshore wind alone is remarkable: marine mammal observers monitoring environmental impacts, UXO divers clearing unexploded ordnance from seabed sites, cable jointers connecting turbine arrays, rope access technicians maintaining blades, and project engineers coordinating multi-billion-pound developments. Each role requires specialised training, safety certification and often years of experience development.

The government’s Clean Energy Jobs Plan represents the first comprehensive workforce strategy, identifying priority occupations and regional requirements. New initiatives include five Clean Energy Technical Excellence Colleges, £1.2bn skills system investment, and transition support for veterans and North Sea oil and gas workers moving into clean energy roles.

However, skills development operates on multi-year timescales. Apprenticeship programmes require 3-5 years to produce qualified technicians. Degree programmes in engineering and science run 3-4 years. Experienced personnel development through on-the-job training demands even longer horizons. The 2025-2030 window for doubling the clean energy workforce to 800,000 therefore necessitates aggressive recruitment, training deployment and retention strategies commencing immediately.

System Integration: Balancing Variable Generation

As renewable penetration increases toward 95% of electricity generation, system integration complexity intensifies. Wind and solar exhibit temporal and geographic variability, creating periods of surplus generation requiring management and periods of supply deficit requiring backup.

- Electricity storage proves essential for time-shifting generation. The government’s Long Duration Electricity Storage investment support scheme provides revenue certainty for multi-hour to multi-day storage projects. Battery storage addresses minute-to-hour fluctuations with rapid response times, while longer-duration technologies, including compressed air energy storage, liquid air energy storage, and eventually hydrogen storage, manage day-to-week variability.

- Demand flexibility enables consumption alignment with generation availability. Industrial processes with flexible operating schedules, electric vehicle charging timed to utilise off-peak or surplus generation, and smart home systems managing heating and appliance operation all contribute to demand-side response capability.

- Interconnection allows electricity import during domestic generation shortfalls and export during surplus periods. The UK’s growing interconnector capacity, currently approximately 17% of peak demand, enhances system flexibility and enables access to complementary generation profiles across continental Europe.

- Low-carbon dispatchable generation provides reliable supply during periods of low renewable output and high demand. Nuclear baseload, gas with carbon capture, and hydrogen-to-power generation complement variable renewables. The government’s commitment to the Hydrogen to Power Business Model, launching in 2026, provides frameworks for incentivising hydrogen-fired generation capacity.

- Curtailment management represents both mounting challenge and substantial opportunity. Recent data reveals the scale of constraint payments has escalated dramatically: in 2024, 8.3 TWh of wind power was curtailed due to grid congestion, equivalent to powering over two million homes annually. This curtailment volume nearly doubled from 2023’s 4.3 TWh, with the trend accelerating into 2025. In the first half of 2025 alone, Great Britain curtailed 4.6 TWh of renewable energy at a cost of £152m to consumers, with total annual curtailment costs on track to exceed £1bn. The majority (over 86%) originates from northern Scotland, where wind generation capacity has grown substantially faster than transmission infrastructure connecting Scottish generation to English demand centres.

However, this wasted renewable electricity presents a strategic opportunity for power-to-X deployment. Analysis by leading policy institutions demonstrates that curtailed wind in 2022 alone could have produced 118,000 tonnes of green hydrogen, rising to 455,000 tonnes annually by 2029, sufficient to displace two-thirds of the UK’s current 700,000-tonne grey hydrogen consumption. Academic research confirms that electrolysis can recover 12-26% of curtailed renewable power while maintaining grid reliability. While grid expansion through the £80bn transmission investment programme will reduce structural curtailment over time, co-locating electrolysers with constrained wind farms offers an immediate solution, converting otherwise-wasted zero-carbon electricity into storable hydrogen for industrial processes, transport fuels or dispatchable power generation. This approach transforms a costly system inefficiency into productive decarbonisation, although hydrogen production from curtailment alone would be insufficient to economically utilise electrolysers.

Policy Certainty: The Investment Enabler

Investment in long-lived energy infrastructure demands policy stability. Multi-billion-pound offshore wind projects, multi-year electrolyser deployments and transmission network upgrades all depend on confidence that regulatory frameworks, support mechanisms and carbon pricing will persist throughout 25-35 year project lifetimes.

The Climate Change Act 2008, establishing legally binding five-year carbon budgets extending to 2037, provides overarching framework certainty. Since Britain adopted this model, 60 other countries have implemented similar climate legislation, demonstrating international influence and establishing the UK as climate policy innovator.

The CfD mechanism, despite the 2023 AR5 auction failure, remains the primary support scheme for renewable generation. Government commitments to sustained CfD allocation rounds with adequate budgets and strike prices reflecting genuine project economics are essential for maintaining deployment momentum. The 2024 AR6 auction secured 5.3 GW of offshore wind capacity at strike prices reflecting cost inflation and supply chain realities, demonstrating policy learning from AR5’s mistakes.

For hydrogen, the Hydrogen Production Business Model provides 15-year revenue support bridging the gap between low-carbon hydrogen production costs and incumbent fossil fuel prices. Forthcoming Hydrogen Transport and Storage Business Models and Hydrogen to Power Business Model complete the policy architecture enabling integrated hydrogen value chains.

The Zero Emission Vehicle Mandate, requiring 22% of new car sales to be zero-emission in 2024, rising to 80% by 2030, provides regulatory certainty driving automotive sector transformation and charging infrastructure investment.

Critical Path: Actions for 2025-2030

For Britain to deliver on renewable energy and power-to-X ambitions, several priority actions demand urgent implementation:

- Electricity Price Reform – Rebalancing policy costs off electricity bills transforms the economic case for industrial electrification and heat deployment. This single intervention could unlock billions in decarbonisation investment.

- Grid Infrastructure Acceleration – The £80bn transmission programme must accelerate from planning to construction. Streamlined approval processes and strategic planning through Regional Energy Strategic Plans should eliminate infrastructure bottlenecks.

- Offshore Wind Delivery at Scale – AR7 and subsequent CfD rounds must deliver sustained 8-10 GW annual capacity awards with realistic strike prices. Failure to maintain this deployment pace places 2030 targets at severe risk.

- Floating Wind Commercialisation – Developments must progress to demonstrate floating technology at commercial scale, de-risking investments and enabling supply chain development for deep-water sites.

- Hydrogen Business Model Completion – Finalising hydrogen transport, storage and power business models enables integrated value chains. Delays constrain industrial adoption and power sector integration.

- Supply Chain Investment – The £1 billion Clean Energy Supply Chain Fund must deploy strategically to build domestic manufacturing capabilities in turbines, blades, cables and foundations, maximising UK content and export opportunities.

- Skills Development at Unprecedented Scale – Doubling the clean energy workforce by 2030 requires aggressive recruitment and training across all technology areas. Excellence colleges and expanded apprenticeships must deliver qualified personnel at record rates.

- Industrial Strategy Implementation – Commitments to industrial electrification, hydrogen deployment and CCUS infrastructure must translate from documents to operational projects through sustained funding, planning support and regulatory clarity.

Conclusion: Offshore Wind as Economic and Environmental Cornerstone

Britain’s renewable energy revolution has transitioned from aspiration to operational reality. The world’s largest offshore wind farm generates power off Yorkshire. Floating wind projects advance in Celtic Sea waters. Electrolyser factories plan construction in industrial heartlands. Solar installations proliferate nationwide. The UK has demonstrated fossil-fuel-free electricity for record durations while achieving the lowest emissions since the industrial revolution.

Yet this substantial progress proves insufficient for meeting 2030 and 2035 targets without sustained acceleration. The 2025-2030 period represents Britain’s decade of delivery, when offshore wind deployment, power-to-X commercialisation and industrial electrification must reach unprecedented rates.

The economic opportunity is clear: £63bn in government investment catalysing over £50bn in private capital, creating 800,000 jobs across coastal regions and industrial communities, and positioning Britain as clean energy exporter and technology leader. Offshore wind alone will contribute £6bn from single projects, with the cumulative sector value approaching £100bn by 2040.

The pathway exists. Offshore wind technology delivers proven performance at decreasing cost. Floating platforms unlock deeper water resources. Power-to-X provides solutions for genuinely hard-to-abate sectors. Grid infrastructure programmes address connection bottlenecks. Skills initiatives train the workforce required for deployment at scale.

Recent data demonstrates Britain has already achieved what once seemed impossible: majority-renewable electricity, sustained periods of 100% clean power, and offshore wind as the dominant generation source. Consumer savings from wind deployment exceed £100bn after accounting for all subsidies, demonstrating economic as well as environmental value.

The next five years determine whether these milestones represent the beginning of sustained transformation or the high-water mark of ambition constrained by delivery realities. For those in the offshore wind sector, for investors assessing opportunities, and for policymakers shaping frameworks, the message is unambiguous: the UK has established comprehensive strategies and substantial financial backing for its renewable energy transition, with offshore wind positioned as the cornerstone technology driving both decarbonisation and industrial renewal.

The opportunity exists for those prepared to execute at pace, navigate delivery complexities and commit to long-term value creation in Britain’s offshore wind-powered clean energy future.

Analysis based on UK Government Carbon Budget and Growth Delivery Plan (October 2025), Climate Change Committee Progress Report (2025), and independent energy sector analysis. All views represent independent assessment of publicly available information.

Sources:

Analysis: Great Britain has run on 100% clean power for record 87 hours in 2025 so far (Carbon Brief, 26 Sep 2025)

Analysis: UK’s solar power surges 42% after sunniest spring on record (Carbon Brief, 4 Jun 2025)

Carbon Budget and Growth Delivery Plan (UK Government, 29 Oct 2025)

Economic impact of NERC on the development of UK offshore wind (UK R&I/NERC, 30 Jun 2025)

Energy Trends, UK, April to June 2025, Statistical Release (UK DESNZ, 30 Sep 2025)

Hydrogen Update to the Market (UK DESNZ, Jul 2025)

Modelling the long-term financial benefits of UK investment in wind energy generation (O’Shea and others, UCL Open Environment, 23 Oct 2025)

Offshore wind farm developers offer millions in funding to new UK supply chain companies (OWIC, 27 Oct 2025)

Offshore wind industry unveils Industrial Growth Plan to create jobs, triple supply chain manufacturing and boost UK economy by £25 billion (The Crown Estate/Renewable UK, 17 Apr 2024)

Press release: Clean energy and jobs from publicly-owned Great British Energy (UK DESNZ, 16 Sep 2025)

Press release: Government unlocks floating offshore wind with major investment for Scottish port (UK DESNZ, 5 Mar 2025)

Progress in reducing emissions – 2025 report to Parliament (Climate Change Committee, Jun 2025)

Record increase in offshore wind capacity critical to Clean Power 2030 goal (OEUK, 15 May 2025)

UK economy to receive £6.1 billion boost from the world’s largest offshore wind farm according to new report (Dogger Bank Wind Farm, 6 Nov 2025)

UN Climate Change Conference – Belém (UNFCCC, Nov 2025)

Unlocking the benefits of the clean energy economy (UK Government, Oct 2025)